At the

beginning of the 21st century it seems that the relationship between the

Eastern and Oriental Orthodox communities is as close as it has been for

centuries. There certainly remain those within the Eastern Orthodox community

who perhaps view the Oriental Orthodox community through a prism of lack of

knowledge and misrepresentation, some of which is due to the lack of proper

explanation by the Oriental Orthodox themselves. But increasingly it has become

impossible for Eastern Orthodox to doubt that Oriental Orthodox have always

confessed the perfect and complete humanity of Christ. In a growing number of

congregations around the world there is a pastorally based reception to

communion of lay members from other Orthodox communities. While formal

agreements allowing communion between various Orthodox communities, and even

proposals for reunion from senior Eastern and Oriental Orthodox hierarchs,

suggest that an opportunity to explore the possibility of unity has now

presented itself as both a challenge and encouragement.

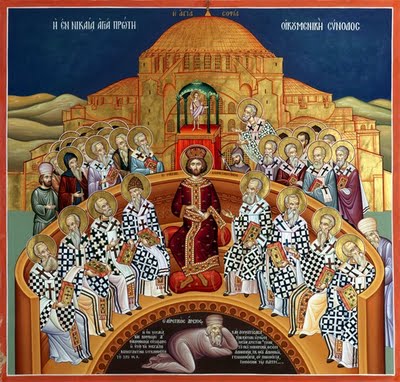

Despite

the positive outcome of the dialogues between the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox

communions over the last decades, it seems clear that an outstanding and

significant issue remains the status of those councils not received by the

Oriental Orthodox. These form such an important aspect of the life and witness

of the Eastern Orthodox communion that they cannot easily be ignored. Recent

agreements produced by the theological dialogue between the Eastern and

Orthodox communities have appeared to skate over the need for a formal response

from the Oriental Orthodox to these later councils.

Nevertheless,

the Oriental Orthodox and Eastern Orthodox have been able to produce a Joint

Agreement which confesses a mutual confidence that the same Christology has

always been held by all. That being so, it must be the case that the later

councils of the Eastern Orthodox, and even the most controversial texts such as

the Tome of Leo, are all able to be understood in an Orthodox manner. These

joint statements have been accepted by the Holy Synods of almost all the

Oriental Orthodox churches and therefore represent a formal and official view

of the Eastern Orthodox.

This

seems to be a moment in history that calls for generous efforts to resolve

centuries old disputes. If it is necessary to go that extra mile in the name of

truth and love, then such demands must be embraced.

I have

been a member of the British Orthodox Church within the Coptic Orthodox

Patriarchate for over twenty years. Even before I became Orthodox I was engaged

in the consideration of the controversy between the Eastern and Oriental

Orthodox communities, and it has continued to be one of the most important

areas of my own research and study. To be able to write about the unhappy

separation of those Orthodox Christians who believe and practice the same faith

requires some detailed understanding of the controversial issues, and of the

historical consequences of events taking place over 1500 years ago.

This

paper is part of a wider project to consider and respectfully present proposals

aimed at encouraging the reconciliation of the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox

communities. In this particular study it will be considered whether the

Oriental Orthodox can receive the Eastern Orthodox councils in some formal

manner. I believe it is both possible and necessary, and that such a reception

can take place without the Oriental Orthodox abandoning our own consistency of

faith and continuity of history.

It will

be necessary to consider the Tome of Leo, the councils of Chalcedon, the Second

of Constantinople, the Third of Constantinople and the Second of Nicaea. If we

must accept them for the sake of reconciliation then how are we to accept them

without sacrificing our own integrity? This paper will describe one perspective

in the following pages.

There

are two aspects of each of these still controversial councils and texts. On the

one hand there is the actual historical event itself, situated in a particular

context and represented by a variety of particular narratives, whether positive

or negative. On the other hand there is the present interpretation of the

different doctrinal, canonical and disciplinary components of these councils.

Is it necessary that all of these components and their historical

representation be viewed in the same way?

Clearly

any event or text can be and is often understood and described in a variety of

manners. The Formula of Reunion of 433 AD brought about the union of St Cyril

and the moderate Antiochians. A certain lexical compromise on both sides

allowed the Orthodox Christology of St Cyril to be confirmed together with an

appropriate breadth of language that allowed the Antiochians to be comfortable

in expressing the same truths.

But when

Ibas of Edessa wrote his letter to Maris the Persian he understood the Formula

of Reunion in an entirely different manner. According to his interpretation of

the correspondence between St Cyril and John of Antioch he wrote,

For Cyril

has written Twelve Chapters, as also I think Your Piety knows, in which he says

that there is one nature constituting the Divinity and Humanity of Our Lord

Jesus Christ….But how impious such statements are Your Piety will have been

quite persuaded…The Lord had willed the subduing of the heart of the Egyptian.

It is

well worth considering the letter of Ibas to Maris the Persian, and noting that

he viewed St Cyril’s Twelve Chapters as error. More than that, he understood

that the Reunion was on the basis of St Cyril rejecting his error and adopting

a Christology which was consistent with the teaching of Theodore of Mopsuestia.

This could hardly be further from the truth, not least because St Cyril was

engaged in writing a work against the Christology of both Theodore of

Mopsuestia and Diodore of Tarsus. But it does illustrate the fact that a single

text can be understood in a variety of ways.

If we

were able to have a conversation with Ibas it would not be enough for us to say

that we agreed with him in accepting the Formula of Reunion of 433. We would

have to ask him how he understood this text, and what Christology it was

endorsing. In this case we would find that though we both seemed to accept the

Formula, in fact what we were confessing were entirely contradictory and

irresolvably different interpretations of what the Formula represented.

What is

actually believed must take priority over the endorsement or criticism of

various texts, such as the Formula of Reunion because apparent agreement can

actually mask an absolute disagreement. While apparent disagreement can in fact

obscure a fundamental agreement.

Now if

it has already been established over decades of dialogue that the Eastern

Orthodox communion shares the same Faith as the Oriental Orthodox communion

then it is not possible to insist that those fundamental, but controversial,

texts and councils which are necessary to the Eastern Orthodox tradition

actually and materially represent a false and even heretical Faith. The Eastern

Orthodox cannot both profess the fullness of the Orthodox Faith and also

profess error in these texts and councils.

Therefore

it must be possible to accept these texts and councils in a manner which is

consistent with the Orthodox Faith, and if it is possible to accept them in an

Orthodox manner then it must also be possible for the Oriental Orthodox to

receive them as Orthodox. This surely requires more than a simplistic assent to

them without an appropriate process of reception, just as simply passing over

them in silence has not proved satisfactory.

But what

do we mean by accepting these texts and councils? In the first place we do not

mean that we will be able to accept the current narrative which many of the

Eastern Orthodox use to locate these texts and events in an historical context.

We have a different view of what happened in many cases, and we believe that

our variant narrative is as justified by historical evidence as any other. It

is not possible for us to say, “Sorry, we have been wrong about everything all

along”, because we do not believe this to be the case. But neither do we wish

to demand of the Eastern Orthodox that they abandon their own understanding of

history as a necessary precondition for reconciliation.

What is

surely required is a certain degree of self-reflection that allows all sides to

understand how the various views of texts and councils came about. This

self-reflection must also extend to an appreciation that different views on

historical events is not a dogmatic matter.

There is

some controversy at present, for example, within both Eastern and Oriental

Orthodoxy, about the consideration of the Emperor Constantine as a saint. It

has been noted that he was not canonised until relatively late, and as part of

a cultus that focused on the city of Constantinople. There is also the issue

that he was baptised only shortly before his death, and had been complicit in

the murder of family members. Is he a saint or not? Does it matter that he

became a saint only centuries after his death? These are questions that often

lead to heated arguments. But the example is raised because having different

views about an historical person, even one whom many consider a saint, does not

lead to a breach of communion, and is not considered as having a dogmatic

character. Is the Emperor Constantine a saint or not? There are those who are

committed to Orthodoxy who hold both opinions.

Those

who believe that there is no scope at all in Orthodoxy for any difference of

opinion on any matter are fortunately in a tiny minority. For most of Orthodoxy

and for most of the time, there has been a understanding that there must be

unity in dogmatic matters, while allowing a variety of opinions, within the

boundary of the Faith, on other matters.

In

regard to the controversial texts and councils that Eastern and Oriental

Orthodox must come to terms with, there are various aspects that warrant

different approaches. In terms of historical context there will perhaps remain,

for a while, distinct narratives that colour the reception of the event itself.

Modern scholars such as Richard Price, in his outstanding editions of the Acts

of Chalcedon and of Constantinople II, have assisted in the process of

developing a more neutral and objective history of these events. The

understanding that these events were more complex than the brief paragraphs

used to describe them in works of catechesis will help to produce an

appreciation that in fact different views of the history usually represent the

fact that there were different agendas that were actually being played out at

these events, and that there is no one monolithic history.

If it is

required that Oriental Orthodox accept unchallenged the popular Eastern

Orthodox historical narrative then reconciliation will continue to be stalled

at an official level. But there is no reason why this should be so. When St

Cyril and John of Antioch were reconciled with each other it was not on the

basis of John of Antioch confessing that he was wrong to hold another separate

council in Ephesus in 431. It was not on the basis of confessing that

everything he remembered of the events was in error. It was on the basis of

accepting the dogmatic substance of St Cyril’s council. It was entirely

reasonable for John of Antioch to continue to believe that St Cyril had acted improperly

at Ephesus, and for him also to accept the deposition of Nestorius and the use

of the term Theotokos in relation to the Virgin Mary.

To

accept these texts and councils does not require the acceptance of a particular

history. But these councils also produced disciplinary statements. These are

also problematic for the Oriental Orthodox since they name some of our own

Fathers such as St Dioscorus and St Severus. But it would seem to many,

including Eastern Orthodox, that these disciplinary resolutions are also not a

matter of dogma. At the council of Ephesus, John of Antioch was deposed by St

Cyril and the bishops with him, yet St Cyril was reconciled with him and did

not act towards him as a bishop who had been deposed, even though an ecumenical

council had disciplined him in such a manner.

Likewise,

Theodore of Mopsuestia died in the peace of the Church, and even St Cyril did

not demand that his name be removed from the diptychs of the Antiochian Church

for the sake of unity, even though he considered him a heretic. Nevertheless at

Constantinople II he was condemned and the approach taken by the Fathers of the

previous generation was modified. There are those Eastern Orthodox who will

insist that any action taken by the Fathers may not be challenged, but this was

clearly not the view of the Fathers themselves, who used different approaches

in different circumstances.

St

Dioscorus was clearly not condemned for heresy in his lifetime but was deposed

on a procedural point. He was anathematised centuries after his martyrdom when

those who so condemned him could have had no real knowledge of his teachings,

which can be seen to be entirely Orthodox by the documentary evidence available

to us. Likewise, St Severus was engaged in dialogue with the Imperial Church

late into his life, and during the 6th century it had been recognised on

several occasions during such official conferences that there was no

Christological difference between those who accepted Chalcedon and those who

rejected it. St Severus was willing to accept the Henotikon as far as it went,

which makes the accusations against him of being both a Nestorian and a

Eutychian especially objectionable.

What we

require of the Eastern Orthodox is a willingness to consider again whether the

condemnations of St Dioscorus and St Severus are properly attached to their

persons, even if the errors purported to have been held by them are certainly

liable to condemnation. There will be a need for the Oriental Orthodox to

consider again the persons of Leo of Rome and the Emperor Justinian. The case

of the Emperor Constantine surely shows that agreement in the canonisation of

various figures is not necessary for agreement in faith, especially not if

there is an agreement in the rejection of those errors some believe these

figures held, and agreement in the acceptance of those truths which others

would wish to insist they held.

These

are not dogmatic matters, they are liable to revision because they depend on

the attribution of error and truth to a particular person, and not on any

acceptance of error or rejection of truth. To a great extent this has already

been understood. When I read the writings of Maximos the Confessor, for

instance, I find myself agreeing with his positive statements of truth and with

his negative criticism of error. But I know that he is entirely wrong to

attribute error to St Severus and that he has mistaken and misrepresented what

St Severus taught. At the time in which Maximos wrote, the works of St Severus

had been entirely proscribed and destroyed within the Empire. They are

preserved to us thanks to the copies made into Syriac even while he was alive. To

disagree with Maximos on a matter of truth and error would have a dogmatic

significance, but to disagree with him when he attributes error to St Severus

is a different matter altogether and is to do with opinion not doctrine.

The very

fact that the Alexandrian Churches, Greek and Coptic, allow intercommunion of

laity, and that the Syrian Churches, Greek and Syriac, experience even closer

ties of mutual fellowship, indicates that the issue of the status of those

controversial persons is not considered to be a doctrinal issue. If the

veneration of St Dioscorus absolutely meant that the Oriental Orthodox accepted

the heresy of Eutyches there could be no such intercommunion. Likewise if the

veneration of Leo of Rome absolutely meant that the Eastern Orthodox accepted

the heresy of Nestorius there could be no such intercommunion. Metropolitan

Hilarion, one of the most senior hierarchs of the Moscow Patriarchate, also

believes that issues such as these are secondary to the profession of the same

doctrinal substance.

What

does this mean? If the historical perspective is not dogmatic, and if the

disciplinary actions are not absolute, then to properly consider the status of

these texts and councils within the Oriental Orthodox communion means to

reflect on the Definitions and official Statements of each council, and those

canons which these councils produced.

Such a

reflection may even comprehend even the most controversial texts such as the

Tome of Leo and the Definition of Chalcedon. We are not asking ourselves do we

agree with everything that has happened in history around these texts, but we

are asking whether the manner in which the Eastern Orthodox understand the

words of these texts is a manner in which we can agree.

If we

were to consider the Sentence and the Capitula of the Second Council of

Constantinople we would discover that there is little in which there could be

any disagreement at all. If we were to consider the Definition of Chalcedon

there are aspects which it is well known would cause some concern. What is

required of us is not to imagine ourselves into the minds of those who accepted

this text in the 5th century, nor even to imagine ourselves into the minds of

our own Fathers who had reasons enough to reject it then. But to discover how

the Eastern Orthodox today, with whom we are challenged to rediscover our

fundamental unity, actually understand this text and all the others.

Once

again it must be insisted that since we confess that the Eastern Orthodox have

the same Christological Faith as ourselves then even the Definition of

Chalcedon must be able to be understood in an Orthodox manner. And if it is

understood in an Orthodox manner then we can receive that interpretation as

Orthodox ourselves.

What

should we do? I believe that a document must be compiled which contains all of

these authoritative texts which cannot be ignored if reconciliation is to take

place. These texts must be glossed or explained with various notes so that it

is clear how we are willing to receive each passage, and which errors and false

readings we wish to exclude. This would not be a very lengthy document, the

output of the various Eastern Orthodox councils is not excessive and deals with

particular issues. This document, however it was produced, and I am researching

just such a volume myself, with an introductory essay and doctrinal and

historical notes, could be received in due course by each of the Synods of the

Oriental Orthodox Churches. This comprehensive text would be accepted as

Orthodox, and as consistent with the Orthodox Faith as professed in the first

three Ecumenical Councils of universal acceptance.

Would

this count as accepting these texts and councils as Ecumenical? The latter

councils after Chalcedon might perhaps be considered ecumenical under such a

process, to the extent of receiving the doctrinal statements and canons. It

would remain problematic to use the term ecumenical of Chalcedon, even under a

narrow consideration of the texts as understood by the Eastern Orthodox at

present. There might be greater consistency in allowing that the acceptance of

a comprehensive document as being Orthodox allows for the reception of all the

doctrinal substance of these councils, including Chalcedon, when properly

understood.

It would

then be possible to say to our partners in dialogue that we do accept all the

ecumenical councils, even if we do not count them all as properly Ecumenical.

This

will not satisfy all Eastern Orthodox. Some do wish to see the complete

submission of all Oriental Orthodox to the historical narrative commonly

presented among those who accept Chalcedon. Some will continue to demand the

condemnation and rejection of St Dioscorus and St Severus as the cost of an

asymmetrical reconciliation. But these are not the majority. There are also

those Oriental Orthodox who believe that our own historical views of

Chalcedonians are immutable, but this is to fail to properly research our own

engagement in efforts for reconciliation in the 5th to 7th centuries.

What is

clear is that we cannot hope to achieve reconciliation without properly coming

to terms with the central place which these texts and councils hold in the

Eastern Orthodox tradition. If there is a need to go that extra mile then we

must take it, while preserving our own integrity. We will discover that even

the most controversial texts can be understood in a variety of ways, and that

in fact we already share agreement in those things which these texts strive to

explain.

There is

continuing hope for reconciliation. But we will not move forward without honestly

considering how to understand these things in an Orthodox manner. I hope to

return to this theme in much greater detail in further and more substantial

papers.

I have a question?if chalcedon accepted the letter of ibas as orthodox,how can we ever say it can be interpreted in a orthodox manner?

ReplyDelete